From War to Peace

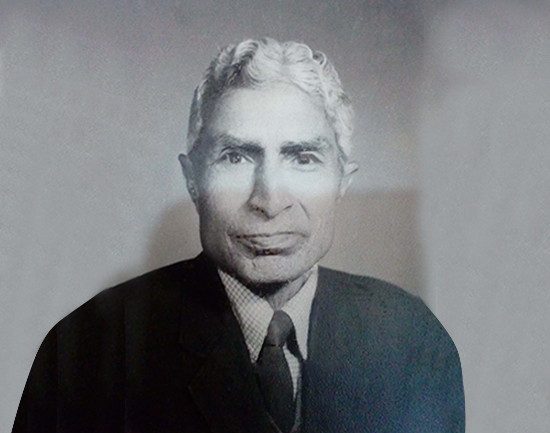

We had a chance of meeting with a 1947 war-veteran, or shall we say a veteran of the great Indian partition. He faced a do-or-die situation during the Sino-Indian Border Conflict. It was emotional listening to his narratives, at times we smiled, at others we cringed. Altogether, we thought it can make a good read for our readers as well. Here he goes, telling you the stories of the horrid times:

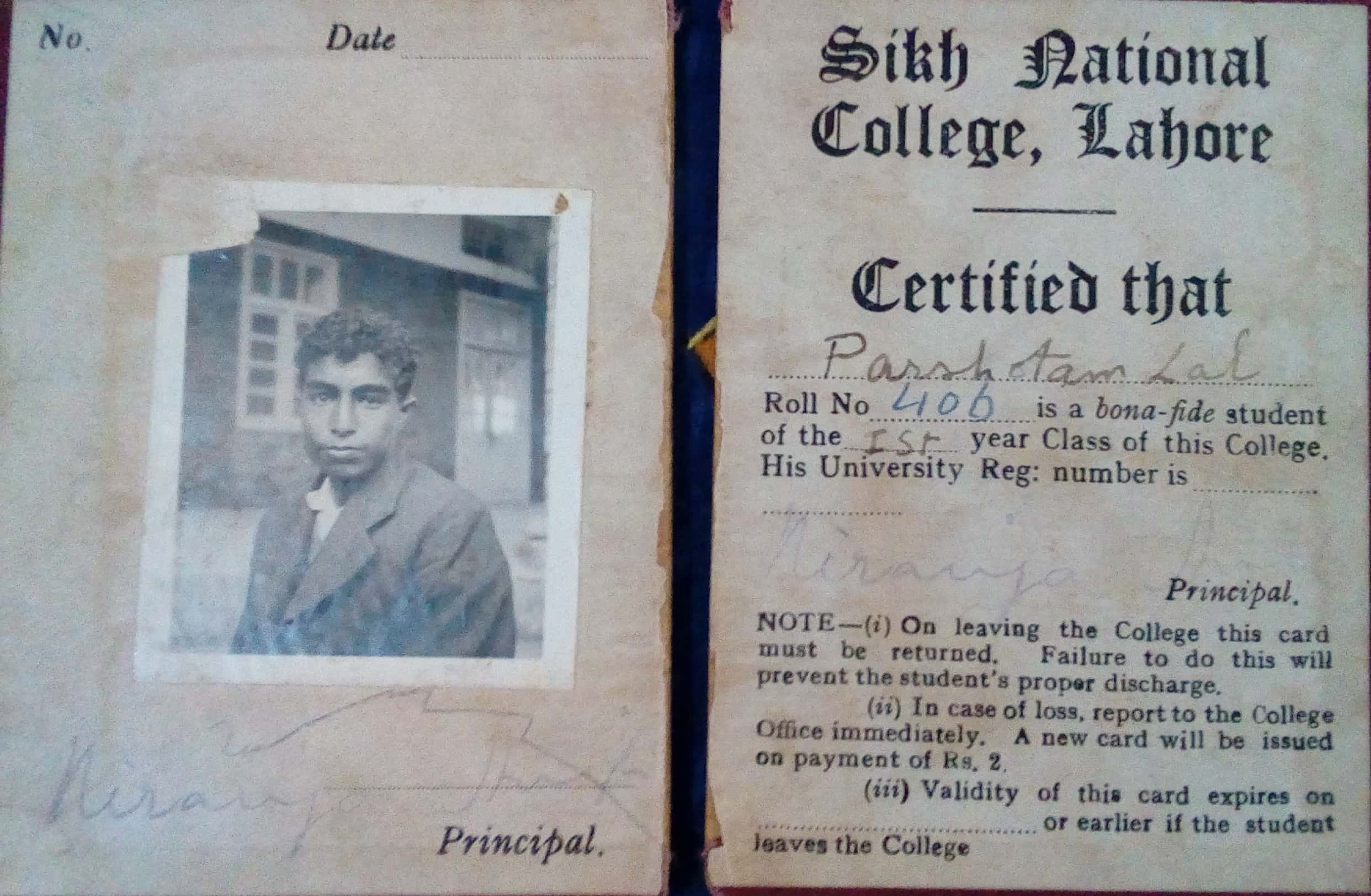

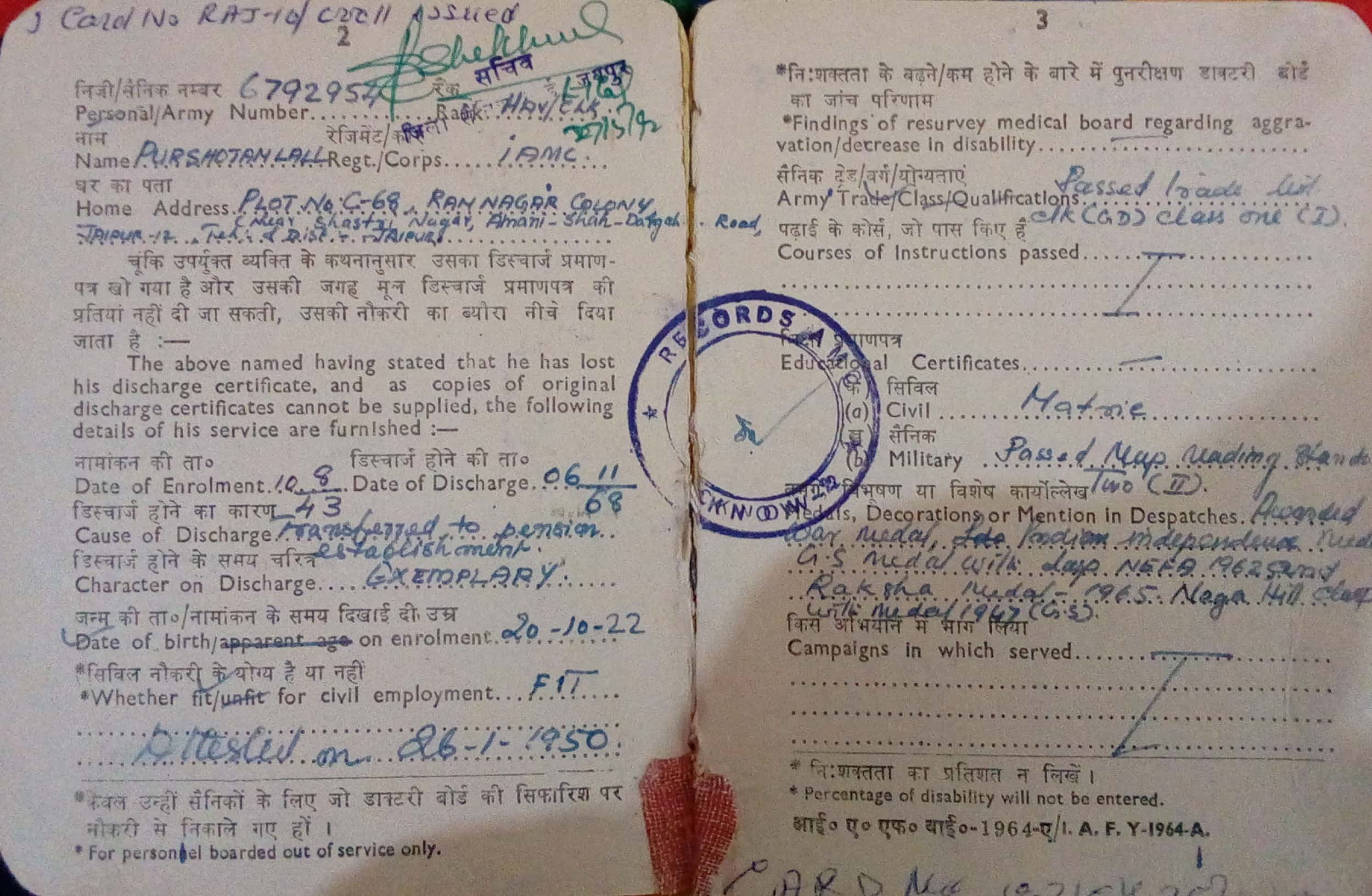

When I was born in pre-independent Punjab region of a united India, it was a beautiful place to be in; I still hold several dear memories. I had studied in Eminabad and Nawanshahr; the two the world for me. Like any typical child of the times, I was practically oblivious of other parts of the country. I loved playing Cricket, Hockey and Football, something I pursued till my graduation; Sikh National College, Lahore, that’s where I studied, I still remember the vast and green premises of the college. Right after my graduation, on my father’s advice who was a Station Master Officer, I joined the Army Medical Corps in August 1943. At age 21, I had a rank equivalent to sergeant.

Though being of worth for your nation has always been a matter of prestige, working for the Indian-British army was quite the opposite, it hurt the self-esteem. While posted in Peshawar, it became very obvious to me that the British soldiers were given far better facilities than us. They had fans to beat the heat but not us, not even electricity; they had quilts against the chills of winters but not us. In fact, we had different wings; their was equipped with many more facilities. Their pay cheques had four-times better numbers than us, for the same ranks too.

Everything was pushing us to a saturation point, when the news of independence started doing rounds. There was a wave of happiness, I heard, not only in my work field but in the entire nation. Who knew it was to be short lived?

By 1946, communal tension had started igniting fires. I remember, while I was posted in one of the hospitals in Peshawar, a group of Hindu women was forced to march nude on a public street, which hurt the Hindu sentiments. Bloodshed was next. At around the same time, my friend’s brother-in-law was stabbed. Soon, I decided to leave Peshawar and be with my father, posted near Pathankot.

Being one among the lucky few who had survived those communal riots, as I reached Jalandhar, the railway station stunned me – the train was all in blood, dead bodies covered the station and in the train was not even a single living being. Who had killed whom? I couldn’t guess, all I have in mind is blood and dead bodies. I was astound as to how my family was left untouched when millions were not! My elder brother was missing and his wife was hysterical; she feared the worst.

By 1946, communal tension had started igniting fires. I remember, while I was posted in one of the hospitals in Peshawar, a group of Hindu women was forced to march nude on a public street, which hurt the Hindu sentiments. Bloodshed was next. At around the same time, my friend’s brother-in-law was stabbed. Soon, I decided to leave Peshawar and be with my father, posted near Pathankot.

Being one among the lucky few who had survived those communal riots, as I reached Jalandhar, the railway station stunned me – the train was all in blood, dead bodies covered the station and in the train was not even a single living being. Who had killed whom? I couldn’t guess, all I have in mind is blood and dead bodies. I was astound as to how my family was left untouched when millions were not! My elder brother was missing and his wife was hysterical; she feared the worst.

When people were going away from the borders, my destiny pulled me back to it: my younger brother and I decided to cross the border, enter into newly built Pakistan, find our brother, a herculean task. My mother, however, didn’t want to trade two of her sons with the war to find one. But we did go, we had to!

My uniform came in handy. Gorkha Rifles, helping Hindus to India, seeing me in uniform, helped me cross the border. We pedaled around for a couple of days and finally found him around 100 kms away from home in Sialkot. What happens when you meet your brother whom you thought you lost to partition? We returned to the safety of our new home. The family reunion was extremely emotional but contented us. Many relatives and friends would reach us from riot-affected areas, which took me to think of the several others who had lost their loved ones.

I decided to rejoin the army to help them. Communication back then was difficult, there were no phones or emails; I wrote a letter to the Indian Army Headquarters in Pune stating my interest to continue serving the nation and – while I waited for their reply – I volunteered to help the people for whom coming to India was a challenge from Pakistan. I feel proud of the fact that our small battalion crossed the border to rescue a group of Hindus struggling in Dera Ismail Khan, deep inside Pakistan.

Once we were back, I headed to Pune for I hadn’t heard from the Army Headquarters; however, my family did receive the letter asking me to join the military hospital in Kangra, though I was already on the way to Pune. Once there, I was posted in Kirkee, where I served for two years, from where I moved to Paud, Pithoragarh, Jodhpur, Kohima, Tejpur and Dirang, when Sino-Indian War broke out in 1962.

India was shouting the Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai slogan, while China was building airports, roads and relocating infantry at Sino-Indian border. Our Prime Minister, Pt Nehru, however, took it to be a political game. It was not until the Dirang Dzong attack that we realised what game China had been preparing for. Several thousands of Army personnel were killed, 1,500 went missing and around 4,000 were captured. It was also the time when India was grappled by a weak economy, corruption was its peak, poverty was the commonest of commons. Neither food nor ammunition was sufficient; General BM Kaul ordered us to step back but it was too late. Chinese troops had entered our hospital and fired unceasingly. One of my friends died on the spot. I wasn’t a fighting soldier, but the Army had trained me to take position yet picking up a gun seemed like the most deciding task to me, as a medical guide. But I ultimately had to shoot in self-defiance. We escaped into a dense jungle where we survived two weeks. A small troop of 15, on our own with no food, ammunition, support and direction, reached Tezpur 16 days later.

Post-war, I was posted to Jodhpur and, for the remaining tenure of my service, I stayed in Rajasthan until my retirement on 6 November 1968. It was then that I started playing my second innings of life, a life of peace only to realise now, in my late 90s, that it was an experience to remember. When I see my medals – War Medal, Podium Independence, General Service Medal with NEFA 1962, Raksha Medal 1965 and General Service Medal 1947 with Clasp: Naga Hills – I feel proud to have been there for the country. And it reminds me, had the entire Hindostan not been united, independence wouldn’t have been possible. I often feel that several lost lives have gone in vain for would they have ever dreamt of a country like this? We have independent but are not free.

As shared by Purshotam Lal Nayyar